How Has The Music Industry Been Affected By Digital Downloading And Streaming

The music industry consists of the individuals and organizations that earn money by writing songs and musical compositions, creating and selling recorded music and sheet music, presenting concerts, as well every bit the organizations that aid, train, correspond and supply music creators. Amid the many individuals and organizations that operate in the manufacture are: the songwriters and composers who write songs and musical compositions; the singers, musicians, conductors, and bandleaders who perform the music; the record labels, music publishers, recording studios, music producers, audio engineers, retail and digital music stores, and performance rights organizations who create and sell recorded music and canvass music; and the booking agents, promoters, music venues, road crew, and audio engineers who help organize and sell concerts.

The industry as well includes a range of professionals who help singers and musicians with their music careers. These include, talent managers, artists and repertoire managers, business managers, entertainment lawyers; those who broadcast audio or video music content (satellite, Cyberspace radio stations, circulate radio and TV stations); music journalists and music critics; DJs; music educators and teachers; musical instrument manufacturers; as well as many others. In improver to the businesses and artists at that place are organizations that also play an important part, including musician'southward unions (eastward.g. American Federation of Musicians), non-for-profit performance-rights organizations (eastward.grand. American Guild of Composers, Authors and Publishers) and other associations (e.g. International Alliance for Women in Music, a non-turn a profit organization that advocates for women composers and musicians).

The modernistic Western music manufacture emerged between the 1930s and 1950s, when records replaced sail music equally the most important product in the music business. In the commercial world, "the recording industry"—a reference to recording performances of songs and pieces and selling the recordings–began to be used as a loose synonym for "the music industry". In the 2000s, a majority of the music market is controlled by 3 major corporate labels: the French-endemic Universal Music Grouping, the Japanese-endemic Sony Music Entertainment,[i] and the Us-owned Warner Music Group. Labels exterior of these three major labels are referred to every bit contained labels (or "indies"). The largest portion of the alive music market for concerts and tours is controlled by Live Nation, the largest promoter and music venue owner. Live Nation is a sometime subsidiary of iHeartMedia Inc, which is the largest owner of radio stations in the Usa.

In the first decades of the 2000s, the music manufacture underwent drastic changes with the advent of widespread digital distribution of music via the Internet (which includes both illegal file sharing of songs and legal music purchases in online music stores). A conspicuous indicator of these changes is total music sales: since 2000, sales of recorded music accept dropped off essentially[ii] [3] while live music has increased in importance.[4] In 2011, the largest recorded music retailer in the earth was now a digital, Internet-based platform operated by a computer company: Apple Inc.'s online iTunes Store.[5] Since 2011, the Music Industry has seen consequent sales growth with streaming now generating more acquirement per annum than digital downloads. Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music are the largest streaming services by subscriber count.[half-dozen]

Business structure [edit]

The main branches of the music manufacture are the alive music industry, the recording industry, and all the companies that railroad train, support, supply and represent musicians.

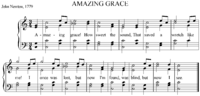

The recording industry produces three split products: compositions (songs, pieces, lyrics), recordings (sound and video) and media (such as CDs or MP3s, and DVDs). These are each a type of property: typically, compositions are owned by composers, recordings by record companies, and media by consumers. In that location may exist many recordings of a single limerick and a single recording will typically exist distributed via many media. For case, the vocal "My Way" is owned by its composers, Paul Anka and Claude François, Frank Sinatra's recording of "My Way" is endemic past Capitol Records, Sid Cruel's recording of "My Fashion" is owned by Virgin Records, and the millions of CDs and vinyl records that can play these recordings are owned past millions of private consumers.

Compositions [edit]

Songs, instrumental pieces and other musical compositions are created past songwriters or composers and are originally endemic past the composer, although they may be sold or the rights may be otherwise assigned. For case, in the case of work for hire, the composition is owned immediately by another party. Traditionally, the copyright owner licenses or "assigns" some of their rights to publishing companies, by means of a publishing contract. The publishing visitor (or a collection gild operating on behalf of many such publishers, songwriters and composers) collects fees (known equally "publishing royalties") when the composition is used. A portion of the royalties are paid by the publishing company to the copyright owner, depending on the terms of the contract. Sheet music provides an income stream that is paid exclusively to the composers and their publishing visitor. Typically (although not universally), the publishing company will provide the owner with an accelerate against hereafter earnings when the publishing contract is signed. A publishing company will besides promote the compositions, such as by acquiring song "placements" on tv or in films.

Recordings [edit]

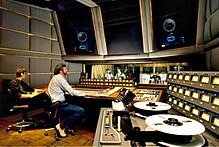

A musician in a recording studio.

Recordings are created by recording artists, which includes singers, musicians (including session musicians) and musical ensembles (e.g. backing bands, rhythm sections, orchestras, etc.) unremarkably with the assistance and guidance from tape producers and audio engineers. They were traditionally made in recording studios (which are rented for a daily or hourly charge per unit) in a recording session. In the 21st century, advances in digital recording technology have allowed many producers and artists to create "home studios" using high-end computers and digital recording programs like Pro Tools, bypassing the traditional role of the commercial recording studio. The record producer oversees all aspects of the recording, making many of the logistic, financial and artistic decisions in cooperation with the artists. The record producer has a range of different responsibilities including choosing material and/or working with the composers, hiring session musicians, helping to adjust the songs, overseeing the musician performances, and directing the audio engineer during recording and mixing to get the best sound. Audio engineers (including recording, mixing and mastering engineers) are responsible for ensuring good audio quality during the recording. They select and set up microphones and use furnishings units and mixing consoles to suit the sound and level of the music. A recording session may also require the services of an arranger, orchestrator, studio musicians, session musicians, vocal coaches, or even a discreetly-hired ghostwriter to help with the lyrics or songwriting.

A studio engineer working with an audio mixer in a recording studio.

Recordings are (traditionally) owned past tape companies. Some artists own their ain record companies (e.k. Ani DiFranco). A recording contract specifies the concern human relationship betwixt a recording creative person and the record visitor. In a traditional contract, the visitor provides an accelerate to the artist who agrees to make a recording that will be owned by the company. The A&R department of a tape company is responsible for finding new talent and overseeing the recording process. The company pays for the recording costs and the price of promoting and marketing the record. For physical media (such as CDs), the company too pays to manufacture and distribute the physical recordings. Smaller record companies (known as "indies") will class business relationships with other companies to handle many of these tasks. The record company pays the recording creative person a portion of the income from the sale of the recordings, besides known equally a "royalty", but this is singled-out from the publishing royalties described to a higher place. This portion is similar to a percentage, merely may be limited or expanded by a number of factors (such equally gratuitous goods, recoupable expenses, bonuses, etc.) that are specified past the record contract. Session musicians and orchestra members (equally well as a few recording artists in special markets) are under contract to provide work for hire; they are typically but paid former fees or regular wages for their services, rather than ongoing royalties.

Media [edit]

Physical media (such equally CDs or vinyl records) are sold by music retailers and are owned by the consumers after they buy them. Buyers do not typically have the right to make digital copies from CDs or other media they buy, or rent or charter the CDs, considering they do not own the recording on the CD, they just ain the individual physical CD. A music distributor delivers crates of the packaged physical media from the manufacturer to the retailer and maintains commercial relationships with retailers and record companies. The music retailer pays the distributor, who in turn pays the record company for the recordings. The record company pays mechanical royalties to the publisher and composer via a collection society. The tape visitor then pays royalties, if contractually obligated, to the recording artist.

When music is digitally downloaded or streamed, there is no physical media other than the consumer's reckoner retentiveness on his or her portable media player or laptop. For this reason, artists such equally Taylor Swift, Paul McCartney, Kings of Leon, and others have chosen for legal changes that would deny social media the right to stream their music without paying them royalties.[7] In the digital and online music market of the 2000s, the distributor becomes optional. Big online shops may pay the labels directly, but digital distributors do be to provide distribution services for vendors big and pocket-size. When purchasing digital downloads or listening to music streaming, the consumer may be required to agree to record visitor and vendor licensing terms beyond those which are inherent in copyright; for instance, some services may allow consumers to freely share the recording, simply others may restrict the user to storing the music on a specific number of hard drives or devices.

Broadcast, soundtrack and streaming [edit]

When a recording is broadcast (either on radio or by a background music service such equally Muzak), performance rights organisations (such as the ASCAP and BMI in the Us, SOCAN in Canada, or MCPS and PRS in the UK), collect a third blazon of royalty known equally a performance royalty, which is paid to songwriters, composers and recording artists. This royalty is typically much smaller than publishing or mechanical royalties. Within the past decade, more than "fifteen to xxx percent" of tracks on streaming services are unidentified with a specific artist. Jeff Price says "Audiam, an online music streaming service, has made over several hundred one thousand dollars in the past year from collecting royalties from online streaming.[8] According to Ken Levitan, manager from Kings of Leon, Cheap Trick and others, "Youtube has become radio for kids". Considering of the overuse of YouTube and offline streaming, album sales have fallen past 60 percent in the past few years.[vii] When recordings are used in television and film, the composer and their publishing company are typically paid through a synchronization license. In the 2000s, online subscription services (such as Rhapsody) also provide an income stream directly to record companies, and through them, to artists, contracts permitting.

Alive music [edit]

A promoter brings together a performing creative person and a venue owner and arranges contracts. A booking agency represents the artist to promoters, makes deals and books performances. Consumers usually purchase tickets either from the venue or from a ticket distribution service such equally Ticketmaster. In the United states of america, Live Nation is the dominant company in all of these roles: they own almost of the big venues in the The states, they are the largest promoter, and they own Ticketmaster. Choices about where and when to tour are decided by the artist's management and the artist, sometimes in consultation with the record company. Record companies may finance a bout in the hopes that it volition help promote the auction of recordings. However, in the 21st century, information technology has become more common to release recordings to promote ticket sales for alive shows, rather than volume tours to promote the sales of recordings.

Major, successful artists volition usually utilise a road coiffure: a semi-permanent touring organization that travels with the creative person during concert serial. The road crew is headed past a tour manager. Crew members provides phase lighting, alive sound reinforcement, musical musical instrument maintenance and transportation. On large tours, the road coiffure may too include an accountant, stage manager, babysitter, hairdressers, makeup artists and catering staff. Local crews are typically hired to assist move equipment on and off stage. On a modest bout with less financial backing, all of these jobs may be handled by merely a few roadies or by the musicians themselves. Bands signed with small "indie" labels and bands in genres such as hardcore punk are more likely to do tours without a road coiffure, or with minimal back up.

Artist direction, representation and staff [edit]

Artists such equally singers and musicians may hire several people from other fields to assist them with their career. The artist manager oversees all aspects of an artist's career in exchange for a percentage of the artist's income. An entertainment lawyer assists them with the details of their contracts with tape companies and other deals. A business concern director handles financial transactions, taxes, and accounting. Unions, such as AFTRA and the American Federation of Musicians in the U.Southward. provide wellness insurance and musical instrument insurance for musicians. A successful artist functions in the marketplace every bit a brand and, as such, they may derive income from many other streams, such as trade, personal endorsements, appearances (without performing) at events or Internet-based services.[9] These are typically overseen by the artist's director and take the class of relationships between the artist and companies that specialize in these products. Singers may also hire a vocal omnibus, dance instructor, acting omnibus, personal trainer or life passenger vehicle to assistance them.

Emerging business organisation models [edit]

In the 2000s, traditional lines that in one case divided singers, instrumentalists, publishers, record companies, distributors, retail and consumer electronics have become blurred or erased. Artists may tape in a home studio using a loftier-cease laptop and a digital recording program such as Pro Tools or use Kickstarter to raise coin for an expensive studio recording session without involving a record company. Artists may choose to exclusively promote and market themselves using only free online video sharing services such as YouTube or using social media websites, bypassing traditional promotion and marketing by a record company. In the 2000s, consumer electronics and computer companies such every bit Apple Computer have become digital music retailers. New digital music distribution technologies and the trends towards using sampling of older songs in new songs or blending different songs to create "mashup" recordings have also forced both governments and the music industry to re-examine the definitions of intellectual property and the rights of all the parties involved. Also compounding the consequence of defining copyright boundaries is the fact that the definition of "royalty" and "copyright" varies from country to country and region to region, which changes the terms of some of these business relationships.

After 15 or and then years of the Internet economy, the digital music industry platforms similar iTunes, Spotify, and Google Play are major improvements over the early illegal file sharing days. However, the multitude of service offerings and revenue models get in hard to sympathize the true value of each and what they can deliver for musicians and music companies. As well, there are major transparency problems throughout the music manufacture caused past outdated technology. With the emerging of new business organisation models as streaming platforms, and online music services, a large amount of data is processed.[x] Admission to big data may increase transparency in the manufacture.[eleven]

History of printed music and recorded music [edit]

Early on history: Printed music in Europe [edit]

Prior to the invention of the printing press, the just way to copy sheet music was past hand, a costly and time-consuming process. Pictured is the hand-written music manuscript for a French Ars subtilior chanson (song) from the late 1300s about dear, entitled Belle, bonne, sage, past Baude Cordier. The music notation is unusual in that it is written in a heart shape, with red notes indicating rhythmic alterations.

Music publishing using machine-printed canvas music developed during the Renaissance music era in the mid-15th century. The development of music publication followed the development of printing technologies that were showtime developed for printing regular books. After the mid-15th century, mechanical techniques for press sheet music were first developed. The earliest example, a set of liturgical chants, dates from about 1465, soon later on the Gutenberg Bible was printed. Prior to this time, music had to be copied out by hand. To copy music notation by hand was a very costly, labor-intensive, and time-consuming process, and so information technology was usually undertaken merely by monks and priests seeking to preserve sacred music for the church building. The few collections of secular (non-religious) music that are extant were commissioned and owned past wealthy aristocrats. Examples include the Squarcialupi Codex of Italian Trecento music and the Chantilly Codex of French Ars subtilior music.

The use of press enabled sheet music to reproduced much more chop-chop and at a much lower cost than paw-copying music notation. This helped musical styles to spread to other cities and countries more quickly, and it as well enabled music to be spread to more than distant areas. Earlier the invention of music printing, a composer's music might simply be known in the city she lived in and its surrounding towns, because simply wealthy aristocrats would be able to afford to have mitt copies made of her music. With music press, though, a composer's music could exist printed and sold at a relatively low cost to purchasers from a wide geographic area. Every bit sheet music of major composer's pieces and songs began to be printed and distributed in a wider area, this enabled composers and listeners to hear new styles and forms of music. A German composer could buy songs written by an Italian or English composer, and an Italian composer could buy pieces written by Dutch composers and learn how they wrote music. This led to more blending of musical styles from unlike countries and regions.

The pioneer of modernistic music printing was Ottaviano Petrucci (built-in in Fossombrone in 1466 – died in 1539 in Venice ), a printer and publisher who was able to secure a twenty-year monopoly on printed music in Venice during the 16th century. Venice was i of the major concern and music centers during this catamenia. His Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, a collection of chansons printed in 1501, is commonly misidentified as the starting time book of sheet music printed from movable type. That stardom belongs to the Roman printer Ulrich Han'southward Missale Romanum of 1476. Nonetheless, Petrucci's later work was boggling for the complexity of his white mensural notation and the smallness of his font. He printed the first book of polyphony (music with ii or more contained melodic lines) using movable type. He also published numerous works past the most highly regarded composers of the Renaissance, including Josquin des Prez and Antoine Brumel. He flourished by focusing on Flemish works, rather than Italian, every bit they were very popular throughout Europe during the Renaissance music era. His printing shop used the triple-impression method, in which a sheet of newspaper was pressed three times. The first impression was the staff lines, the second the words, and the tertiary the notes. This method produced very clean and readable results, although it was time-consuming and expensive.

Until the 18th century, the processes of formal limerick and of the press of music took place for the virtually part with the back up of patronage from aristocracies and churches. In the mid-to-late 18th century, performers and composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart began to seek more than commercial opportunities to market place their music and performances to the general public. After Mozart's death, his married woman (Constanze Weber) connected the procedure of commercialization of his music through an unprecedented series of memorial concerts, selling his manuscripts, and collaborating with her second husband, Georg Nissen, on a biography of Mozart.[12]

An instance of mechanically printed sheet music.

In the 19th century, sheet-music publishers dominated the music industry. Before the invention of sound recording technologies, the main way for music lovers to hear new symphonies and opera arias (songs) was to buy the sheet music (oft arranged for piano or for a pocket-sized chamber music group) and perform the music in a living room, using friends who were amateur musicians and singers. In the United States, the music industry arose in tandem with the rise of "blackness confront" minstrelsy. Greasepaint is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-black performers to represent a black person. The practice gained popularity during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of negative racial stereotypes of African-American people.[thirteen]

In the late function of the century the group of music publishers and songwriters which dominated pop music in the United States became known equally Tin Pan Aisle. The name originally referred to a specific identify: West 28th Street between 5th and 6th Avenue in Manhattan, and a plaque (see beneath) on the sidewalk on 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth commemorates it. The start of Tin Pan Alley is usually dated to about 1885, when several music publishers gear up store in the same district of Manhattan. The end of Can Pan Alley is less clear-cut. Some engagement it to the start of the Great Depression in the 1930s when the phonograph and radio supplanted sheet music every bit the driving force of American popular music, while others consider Tin Pan Aisle to take continued into the 1950s when before styles of American popular music were upstaged by the rise of rock & curl.

Advent of recorded music and radio broadcasting [edit]

A radio broadcasting organization from 1906.

At the dawn of the early 20th century, the evolution of sound recording began to function equally a disruptive technology to the commercial interests which published sheet music. During the canvas music era, if a regular person wanted to hear pop new songs, he or she would buy the canvas music and play it at home on a piano, or learn the song at home while playing the accompaniment part on piano or guitar. Commercially released phonograph records of musical performances, which became available starting in the late 1880s, and later the onset of widespread radio broadcasting, starting in the 1920s, forever changed the way music was heard and listened to. Opera houses, concert halls, and clubs continued to produce music and musicians and singers connected to perform alive, just the power of radio allowed bands, ensembles and singers who had previously performed only in one region to become popular on a nationwide and sometimes even a worldwide scale. Moreover, whereas attendance at the top symphony and opera concerts was formerly restricted to loftier-income people in a pre-radio globe, with broadcast radio, a much larger wider range of people, including lower and middle-income people could hear the all-time orchestras, big bands, pop singers and opera shows.

The "tape manufacture" somewhen replaced the sheet music publishers as the music industry'due south largest force. A multitude of record labels came and went. Some noteworthy labels of the before decades include the Columbia Records, Crystalate, Decca Records, Edison Bong, The Gramophone Visitor, Invicta, Kalliope, Pathé, Victor Talking Motorcar Visitor and many others.[xiv] Many record companies died out as quickly every bit they had formed, and by the end of the 1980s, the "Big six" — EMI, CBS, BMG, PolyGram, WEA and MCA — dominated the industry. Sony bought CBS Records in 1987 and changed its name to Sony Music in 1991. In mid-1998, PolyGram Music Group merged with MCA Music Entertainment creating what we at present know as Universal Music Group. Since so, Sony and BMG merged in 2004,[xv] and Universal took over the bulk of EMI's recorded music interests in 2012.[16] EMI Music Publishing, likewise once office of the now defunct British conglomerate, is at present co-owned by Sony as a subsidiary of Sony/ATV Music Publishing.[17] Every bit in other industries, the record industry is characterised by many mergers and/or acquisitions, for the major companies besides every bit for middle sized business organization (contempo example is given past the Kingdom of belgium group PIAS and French group Harmonia Mundi).[18]

Genre-wise, music entrepreneurs expanded their industry models into areas like folk music, in which limerick and functioning had connected for centuries on an advertisement hoc self-supporting basis. Forming an independent record label, or "indie" label, or signing to such a label continues to exist a popular option for upwardly-and-coming musicians, particularly in genres like hardcore punk and farthermost metal, even though indies cannot offer the same financial bankroll of major labels. Some bands prefer to sign with an indie label, considering these labels typically give performers more than creative freedom.

Rise of digital online distribution [edit]

| External images | |

|---|---|

| RIAA U.S. Recorded Music Sales Charts (Interactive); Revenue and Volumes past Format. (1973 - ) | |

| | |

| | |

| | |

| |

The logo for Apple Inc.'s online iTunes store, which sells digital files of songs and musical pieces–along with a range of other content, such as digital files of Television shows and movies.

In the first decade of the 2000s, digitally downloaded and streamed music became more than pop than ownership physical recordings (eastward.g. CDs, records and tapes). This gave consumers most "friction-less" admission to a wider variety of music than ever earlier, across multiple devices. At the same time, consumers spent less money on recorded music (both physically and digitally distributed) than they had in the 1990s.[19] Total "music-business" revenues in the U.S. dropped past half, from a loftier of $14.6 billion in 1999 to $six.3 billion in 2009, according to Forrester Research.[20] Worldwide revenues for CDs, vinyl, cassettes and digital downloads fell from $36.ix billion in 2000[21] to $fifteen.9 billion in 2010[22] according to IFPI. The Economist and The New York Times reported that the downward trend was expected to continue for the foreseeable future.[23] [24] This dramatic pass up in acquirement has caused large-scale layoffs inside the industry, driven some more venerable retailers (such every bit Belfry Records) out of business and forced tape companies, record producers, studios, recording engineers and musicians to seek new business models.[7]

In response to the rise of widespread illegal file sharing of digital music-recordings, the record industry took aggressive legal activity. In 2001 it succeeded in shutting downwardly the popular music-website Napster, and threatened legal action against thousands of individuals who participated in sharing music-song sound-files.[7] However, this failed to slow the decline in music-recording revenue and proved a public-relations disaster for the music manufacture.[7] Some academic studies take even suggested that downloads did not crusade the decline in sales of recordings.[25] The 2008 British Music Rights survey[26] showed that 80% of people in U.k. wanted a legal peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing service, still but half of the respondents thought that the music'south creators should exist paid. The survey was consistent with the results of earlier research conducted in the United States, upon which the Open Music Model was based.[27]

Legal digital downloads became widely available with the debut of the Apple iTunes Shop in 2003.[28] The popularity of music distribution over the Cyberspace has increased,[29] and by 2011 digital music sales topped physical sales of music.[xxx] Atlantic Records reports that digital sales accept surpassed physical sales.[23] However, every bit The Economist reported, "paid digital downloads grew rapidly, but did non brainstorm to make up for the loss of revenue from CDs".[24]

After 2010, Internet-based services such as Deezer, Pandora, Spotify, and Apple'due south iTunes Radio began to offer subscription-based "pay to stream" services over the Internet. With streaming services, the user pays a subscription to a company for the right to listen to songs and other media from a library. Whereas with legal digital download services, the purchaser owns a digital re-create of the song (which they tin keep on their computer or on a digital media player), with streaming services, the user never downloads the song file or owns the song file. The subscriber can only listen to the song for as long as they continue to pay the streaming subscription. Once the user stops paying the subscription, they cannot heed to audio from the company's repositories anymore. Streaming services began to have a serious impact on the industry in 2014.

Spotify, together with the music-streaming industry in general, faces some criticism from artists claiming they are not being fairly compensated for their piece of work as downloaded-music sales decline and music-streaming increases. Unlike physical or download sales, which pay a fixed price per song or anthology, Spotify pays artists based on their "market share" (the number of streams for their songs equally a proportion of total songs streamed on the service).[31] Spotify distributes approximately 70% to rights-holders, who volition and then pay artists based on their agreements. The variable, and (some say) inadequate nature of this compensation,[32] has led to criticism. Spotify reports paying on average US$0.006 to Us$0.008 per stream. In response to concerns, Spotify claims that they are benefiting the music business by migrating "them away from piracy and less monetised platforms and allowing them to generate far greater royalties than before" by encouraging users to use their paid service.[33] [34]

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) revealed in its 2015 earnings report that streaming services were responsible for 34.iii per centum of the year's U.S. recorded-music-industry revenue, growing 29 pct from the previous year and becoming the largest source of income, pulling in around $2.4 billion.[35] [36] US streaming revenue grew 57 per centum to $one.six billion in the get-go half of 2016 and deemed for almost half of industry sales.[37] This contrasts with the $14.6 billion in acquirement that was received in 1999 by the U.S. music manufacture from the sale of CDs.

The turmoil in the recorded-music industry in the 2000s altered the twentieth-century residuum betwixt artists, record companies, promoters, retail music-stores and consumers. As of 2010[update], big-box stores such as Wal-Mart and Best Buy sell more records than music-but CD stores, which take ceased to function every bit a major player in the music industry. Music-performing artists at present rely on live performance and merchandise sales (T-shirts, sweatshirts, etc.) for the majority of their income, which in turn has fabricated them more than dependent - like pre-20th-century musicians - on patrons, at present exemplified by music promoters such every bit Live Nation (which dominates tour promotion and owns or manages a large number of music venues).[four] In social club to benefit from all of an creative person'south income streams, tape companies increasingly rely on the "360 deal", a new business-relationship pioneered past Robbie Williams and EMI in 2007.[38] At the other extreme, tape companies can offering a simple manufacturing- and distribution-deal, which gives a higher percentage to the artist, merely does not embrace the expenses of marketing and promotion.

Companies like Kickstarter help contained musicians produce their albums through fans funding bands they want to heed to.[39] Many newer artists no longer see a tape deal as an integral role of their concern plan at all. Inexpensive recording-hardware and -software make information technology possible to record reasonable-quality music on a laptop in a bedroom and to distribute it over the Internet to a worldwide audition.[40] This, in turn, has caused issues for recording studios, record producers and audio engineers: the Los Angeles Times reports that as many equally half of the recording facilities in that city have failed.[41] Changes in the music industry take given consumers access to a wider variety of music than ever before, at a price that gradually approaches zero.[7] However, consumer spending on music-related software and hardware increased dramatically over the concluding decade, providing a valuable new income-stream for technology companies such as Apple Inc. and Pandora Radio.

Sales statistics [edit]

Digital album volume sales growth in 2014 [edit]

According to IFPI,[42] the global digital album sales grew by vi.nine% in 2014.

| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| US | +2.1% |

| UK | −two.8% |

| French republic | −iii.4% |

| Global (est.) | +vi.ix% |

Source: Nielsen SoundScan, Official Charts Company/BPI, GfK and IFPI guess.

Consolidation [edit]

Earth music marketplace sales shares, according to IFPI (2005)

EMI (13.4%)

WMG (eleven.3%)

Sony BMG (21.5%)

UMG (25.5%)

Independent (28.iv%)

Prior to December 1998, the industry was dominated by the "Big Six": Sony Music and BMG had not even so merged, and PolyGram had non yet been absorbed into Universal Music Grouping. After the PolyGram-Universal merger, the 1998 marketplace shares reflected a "Big Five", commanding 77.4% of the market, every bit follows, according to MEI World Study 2000:

- Universal Music Group — 21.ane%

- Sony Music Entertainment — 17.4%

- EMI — 14.i%

- Warner Music Group — 13.iv%

- BMG — 11.4%

- Independent labels combined — 22.6%

In 2004, the joint venture of Sony and BMG created the 'Big Four' at a fourth dimension the global market was estimated at $30–twoscore billion.[43] Full annual unit sales (CDs, music videos, MP3s) in 2004 were 3 billion. Additionally, according to an IFPI report published in August 2005,[44] the big 4 accounted for 71.7% of retail music sales:

- Universal Music Group—25.v%

- Sony BMG Music Entertainment—21.v%

- EMI Grouping—xiii.four%

- Warner Music Group—xi.3%

- Independent labels combined—28.3%

The states music marketplace shares, according to Nielsen SoundScan (2011)

EMI (9.62%)

WMG (nineteen.13%)

SME (29.29%)

UMG (29.85%)

Independent (12.11%)

Nielsen SoundScan in their 2011 report noted that the "big 4" controlled about 88% of the marketplace:[45]

- Universal Music Group (U.s. based) — 29.85%

- Sony Music Entertainment (Us based) — 29.29%

- Warner Music Group (Us based) — 19.13%

- EMI Group — 9.62%

- Independent labels — 12.11%

Later on the absorption of EMI by Sony Music Amusement and Universal Music Grouping in December 2011 the "big three" were created and on Jan 8, 2013 afterwards the merger at that place were layoffs of xl workers from EMI. European regulators forced Universal Music to spin off EMI avails which became the Parlophone Label Grouping which was acquired by Warner Music Group.[46] Nielsen SoundScan issued a report in 2012, noting that these labels controlled 88.5% of the market place, and farther noted:[47]

- Universal Music Group (Usa based) which owns EMI Music — 32.41% + 6.78% of EMI Group

- Sony Music Entertainment (U.s. based) which owns publishing arm of EMI Group — 30.25%

- Warner Music Grouping— 19.xv%

- Contained labels— eleven.42%

Annotation: the IFPI and Nielsen Soundscan use different methodologies, which makes their figures difficult to compare casually, and impossible to compare scientifically.[48]

Current Markets shares as of September 2018 are equally follows:[49]

- Warner Music Group — 25.ane%

- Universal Music Group — 24.3%

- Sony Corporation — 22.1%

- Other — 28.5%

The largest players in this industry own more than than 100 subsidiary record labels or sublabels, each specializing in a sure market niche. Merely the industry's nigh popular artists are signed directly to the major label. These companies account for more than one-half of US market share. Nevertheless, this has fallen somewhat in recent years, as the new digital environment allows smaller labels to compete more finer.[49]

Albums sales and market value [edit]

Full anthology sales accept declined in the early decades of the 21st century, leading some music critics to declare the death of the album. (For example, the but albums that went platinum in the US in 2014 were the soundtrack to the Disney animated film Frozen and Taylor Swift's 1989, whereas several artists did in 2013.)[50] [51] The post-obit tabular array shows anthology sales and marketplace value in the globe in 2014.

Source: IFPI 2014 almanac report.[52]

Recorded music retail sales [edit]

2000 [edit]

In its June xxx, 2000 annual study filed with the U.S. Securities and Commutation Commission, Seagram reported that Universal Music Grouping made xl% of the worldwide classical music sales over the preceding year.[53]

2005 [edit]

Acting physical retail sales in 2005. All figures in millions.

| Country info | Units | Value | Alter (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking | Land proper name | Singles | CD | DVD | Total Units | $ (in USD) | Local Currency | Units | Value |

| 1 | USA | 14.vii | 300.5 | eleven.6 | 326.8 | 4783.two | 4783.2 | −5.70% | −v.thirty% |

| ii | Nippon | 28.5 | 93.7 | 8.5 | 113.5 | 2258.2 | 239759 | −half-dozen.ninety% | −9.xx% |

| 3 | UK | 24.three | 66.viii | 2.9 | 74.8 | 1248.five | 666.7 | −1.70% | −4.00% |

| iv | Germany | 8.5 | 58.vii | 4.4 | 71 | 887.7 | 689.seven | −vii.70% | −five.80% |

| v | France | 11.5 | 47.3 | iv.five | 56.9 | 861.ane | 669.one | 7.fifty% | −2.50% |

| six | Italy | 0.v | fourteen.seven | 0.7 | 17 | 278 | 216 | −8.40% | −12.thirty% |

| vii | Canada | 0.one | twenty.viii | i.5 | 22.3 | 262.9 | 325 | 0.70% | −four.sixty% |

| 8 | Commonwealth of australia | three.6 | fourteen.5 | 1.5 | 17.ii | 259.half dozen | 335.9 | −22.ninety% | −eleven.eighty% |

| 9 | India | – | 10.9 | – | 55.iii | 239.6 | 11500 | −19.20% | −ii.40% |

| x | Espana | 1 | 17.5 | 1.i | 19.i | 231.vi | 180 | −thirteen.40% | −15.70% |

| 11 | Netherlands | 1.2 | 8.vii | 1.9 | xi.one | 190.3 | 147.ix | −31.30% | −19.fourscore% |

| 12 | Russia | – | 25.5 | 0.1 | 42.vii | 187.ix | 5234.7 | −9.40% | 21.twenty% |

| xiii | Mexico | 0.1 | 33.4 | 0.viii | 34.half dozen | 187.ix | 2082.iii | 44.00% | 21.50% |

| 14 | Brazil | 0.01 | 17.6 | 2.iv | 24 | 151.7 | 390.3 | −20.40% | −16.50% |

| 15 | Austria | 0.six | 4.5 | 0.2 | 5 | 120.5 | 93.6 | −1.fifty% | −9.60% |

| 16 | Switzerland ** | 0.8 | 7.1 | 0.ii | vii.viii | 115.8 | 139.2 | n/a | north/a |

| 17 | Belgium | 1.4 | 6.7 | 0.5 | 7.7 | 115.4 | 89.7 | −13.80% | −8.90% |

| 18 | Kingdom of norway | 0.iii | 4.5 | 0.i | 4.viii | 103.4 | 655.vi | −19.lxx% | −10.40% |

| nineteen | Sweden | 0.6 | half-dozen.six | 0.2 | seven.2 | 98.five | 701.1 | −29.00% | −20.30% |

| xx | Denmark | 0.ane | 4 | 0.1 | 4.ii | 73.1 | 423.five | three.70% | −iv.20% |

| Top 20 | 74.5 | 757.ane | 42.eight | 915.2 | 12378.7 | −vi.sixty% | −half dozen.30% | ||

2003–2007 [edit]

Approximately 21% of the gross CD acquirement numbers in 2003 can be attributed to used CD sales.[ citation needed ] This number grew to approximately 27% in 2007.[ commendation needed ] The growth is attributed to increasing on-line sales of used product past outlets such as Amazon.com, the growth of used music media is expected to continue to abound as the cost of digital downloads continues to rise.[ commendation needed ] The auction of used goods financially benefits the vendors and online marketplaces, only in the United states, the first-sale doctrine prevents copyright owners (tape labels and publishers, generally) from "double dipping" through a levy on the sale of used music.

2011 [edit]

In mid-2011, the RIAA trumpeted a sales increase of v% over 2010, stating that "in that location'due south probably no 1 single reason" for the bump.[54]

2012 [edit]

The Nielsen Visitor & Billboard's 2012 Industry Report shows overall music sales increased 3.1% over 2011. Digital sales caused this increase, with a Digital Album sales growth of fourteen.one% and Digital Runway sales growth of 5.1%, whereas Physical Music sales decreased by 12.viii% versus 2011. Despite the subtract, physical albums were still the dominant album format. Vinyl Tape sales increased by 17.7% and Vacation Season Album sales decreased by 7.one%.[47]

Total acquirement by year [edit]

Global merchandise revenue according to the IFPI.

| Year | Revenue | Change | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | $20.seven billion | –iii% | [55] [56] |

| 2006 | $19.half-dozen billion | –5% | [55] |

| 2007 | $eighteen.8 billion | −four% | [57] |

| 2008 | $18.four billion | −two% | [58] |

| 2009 | $17.iv billion | −5% | [59] |

| 2010 | $16.8 billion | −three.four% | [8] |

| 2011 | $16.2 billion | −four% | [eight] [threescore] (Includes sync revenues) |

| 2012 | $16.5 billion | +2% | [sixty] |

| 2013 | $fifteen billion | −nine% | [61] |

| 2014 | $fourteen.97 billion | -0.2% | [62] |

| 2015 | $15 billion | +3.2% | [63] [64] |

| 2016 | $xv.7 billion | +5% | [65] |

| 2017 | $17.4 billion | +10.8% | [65] |

| 2018 | $xix.1 billion | +9.seven% | [65] |

| 2019 | $xx.2 billion | +8.2% | [66] |

By region [edit]

- Music manufacture of Asia

- Music industry of Eastern asia

- Music industry of Northern Europe

- Music industry of the U.Yard.

Associations and organizations [edit]

The List of music associations and organizations covers examples from effectually the world, ranging from huge international bodies to smaller national-level bodies.

See likewise [edit]

- DIY ethic

- History of music publishing

- Independent record label

- List of record labels and Category:Record labels

- Listing of best-selling music artists

- MIDEM-Globe's largest music merchandise fair

- Record label

- Music customs

- White label

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Sony Corporation announced October one, 2008 that it had completed the acquisition of Bertelsmann's 50% stake in Sony BMG, which was originally appear on August 5, 2008. Ref: "Sony's conquering of Bertelsmann's l% Pale in Sony BMG consummate" (Press release). Sony Corporation of America. Archived from the original on October 3, 2008.

- ^ "The Music Industry". The Economist. October 15, 2008.

- ^ Goldman, David (February 3, 2010). "Music'due south lost decade: Sales cut in half".

- ^ a b Seabrook, John (Baronial x, 2009). "The Price of the Ticket". The New Yorker. Register of Entertainment. p. 34.

- ^ "Mobile World Congress 2011". dailywireless.org. Feb 14, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

Amazon is now the earth's biggest book retailer. Apple, the globe's largest music retailer.

- ^ Lee, Tyler; PDT, on 04/05/2020 xv:51. "Spotify Was The Largest Music Streaming Service For 2019". Ubergizmo . Retrieved March iii, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Knopper, Steve (2009). Appetite for Cocky-Devastation: the Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Historic period . Complimentary Printing. ISBN978-1-4165-5215-4.

- ^ a b c "IFPI 2012 Report: Global Music Acquirement Downward 3%; Sync, PRO, Digital Income Upwards". Billboard. March 26, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September ix, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy equally championship (link) - ^ "What a Mess: New Report From Berklee College of Music Looks to Ready an Aging, Fractured Business". Billboard. July 14, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Creating Transparency In The Music Industry". Hypebot.com. August 4, 2015. Retrieved Nov 21, 2016.

- ^ Glover, Jane. "Dear Constanze | Music". The Guardian . Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ For the "darky"/"coon" distinction see, for instance, note 34 on p. 167 of Edward Marx and Laura E. Franey's annotated edition of Yone Noguchi, The American Diary of a Japanese Girl, Temple University Press, 2007, ISBN ane-59213-555-2. See likewise Lewis A. Erenberg (1984), Steppin' Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Civilisation, 1890–1930, University of Chicago Press, p. 73, ISBN 0-226-21515-6. For more on the "darky" stereotype, see J. Ronald Green (2000), Straight Lick: The Movie theatre of Oscar Micheaux, Indiana Academy Press, pp. 134, 206, ISBN 0-253-33753-iv; p. 151 of the same piece of work likewise alludes to the specific "coon" archetype.

- ^ "Early Record Label History". Angelfire.com. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ "Sony and BMG merger backed by EU", BBC News, July nineteen, 2004

- ^ Mark Sweney "Universal's £i.2bn EMI takeover approved – with atmospheric condition", The Guardian (London),

- ^ "Sold! EMI Music Publishing to Consortium Led by Sony/ATV, Michael Jackson Manor for $2.two Billion", The Hollywood Reporter, June thirty, 2012

- ^ Mario d'Angelo: "Does globalisation mean ineluctable concentration?" in Roche F., Marcq B., Colomé D. (eds)The Music Manufacture in the New Economy, Report of the Asia-Europe Seminar (Lyon 2001) IEP de Lyon/Asia-Europe Foundation/Eurical, 2002, pp.53–60.

- ^ McCardle, Megan (May 2010). "The Freeloaders". The Atlantic . Retrieved December x, 2010.

industry revenues have been declining for the past x years

- ^ Goldman, David (February 3, 2010). "Music's lost decade: Sales cutting in one-half". Retrieved December i, 2018.

[...] information technology would appear all is well in the recording industry. But at the end of terminal twelvemonth, the music business was worth half of what information technology was ten years ago and the turn down doesn't await like it will be slowing someday soon. [...] Total revenue from U.S. music sales and licensing plunged to $6.3 billion in 2009, according to Forrester Enquiry. In 1999, that acquirement figure topped $14.6 billion.

- ^ "2000 Manufacture World Sales" (PDF). IFPI almanac report. April 9, 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2011. Retrieved July eighteen, 2011.

- ^ Smirke, Richard (March 30, 2011). "IFPI 2011 Report: Global Recorded Music Sales Fall 8.4%; Eminem, Lady Gaga Top Int'l Sellers". Billboard Magazine . Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Arango, Tim (Nov 25, 2008). "Digital Sales Surpass CDs at Atlantic". The New York Times . Retrieved July half-dozen, 2009.

- ^ a b "The music industry". The Economist. Jan 10, 2008.

- ^ Borland, John (March 29, 2004). "Music sharing doesn't kill CD sales, study says". C Net. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Andrew Orlowski. 80% want legal P2P - survey. The Annals, 2008.

- ^ Shuman Ghosemajumder. Advanced Peer-Based Engineering Business Models. MIT Sloan School of Management, 2002.

- ^ X. Chen, Brian (April 28, 2010). "April 28, 2003: Apple Opens iTunes Store". Wired . Retrieved November xix, 2019.

- ^ Griggs, Brandon (Apr 26, 2013). "How iTunes changed music, and the earth". CNN . Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Segall, Laurie (January 5, 2012). "Digital music sales summit concrete sales". CNN . Retrieved Apr 24, 2012.

According to a Nielsen and Billboard report, digital music purchases accounted for 50.3% of music sales in 2011.

- ^ Marshall, Lee (July 3, 2015). "'Let's keep music special. F—Spotify': on-demand streaming and the controversy over artist royalties". Creative Industries Journal. 8 (ii): 177–189. doi:10.1080/17510694.2015.1096618. hdl:1983/e268a666-8395-4160-9d07-4754052dff5d. ISSN 1751-0694. S2CID 143176746.

- ^ Dredge, Stuart (April 3, 2015). "How much do musicians actually make from Spotify, iTunes and YouTube?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ "Exclusive: Taylor Swift on Being Popular's Instantly Platinum Wonder... And Why She's Paddling Against the Streams". yahoo.com. November six, 2014.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Shuns 'Grand Experiment' of Streaming Music". Rolling Stone. Nov vi, 2014.

- ^ Compare: "News and Notes on 2015 RIAA Shipment and Acquirement Statistics" (PDF). RIAA. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

Combining all categories of streaming music (subscription, advertisement-supported on-need, and SoundExchange distributions), revenues grew 29% to $2.4 billion.

- ^ "Streaming made more revenue for music manufacture in 2015 than digital downloads, physical sales". The Washington Times. Retrieved Jan 5, 2017.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (September 20, 2016). "The Music Industry Is Finally Making Money on Streaming". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg Fifty.P. Retrieved Jan 5, 2017.

- ^ Rosso, Wayne (January 16, 2009). "Perspective: Recording industry should brace for more bad news". CNET. Retrieved Jan 17, 2009.

- ^ "Startups, Not Apple, Lead Music Industry's Rebirth". Thestreet.com . Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Graham, Jefferson (October 14, 2009). "Musicians ditch studios for tech such as GiO for Macs". United states of americaA. Today.

- ^ Nathan Olivarez-Giles (October 13, 2009). "Recording studios are being left out of the mix". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Digital Music Report 2014" (PDF). p. nine. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ According to the RIAA Archived May 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine the world music market is estimated at $forty billion, but according to IFPI (2004) it is estimated at $32 billion.

- ^ "IFPI releases definitive statistics on global market for recorded music". Ifpi.org. August ii, 2005. Archived from the original on Nov 9, 2013. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ "The Nielsen Company & Billboard'southward 2011 Music Industry Report," Business organization Wire (Jan 5, 2012)

- ^ Tom Pakinkis, "EMI lay-offs reported in the United states of america," Music Week (January eight, 2013)

- ^ a b "The Nielsen Company & Billboard's 2012 Music Industry Report," Business concern Wire (Jan 4, 2013)

- ^ "Digital Music Futures and the Independent Music Manufacture", Clicknoise.net, February i, 2007.

- ^ a b IBISWorld written report 51221

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh (Oct 16, 2014). "Not One Artist's Album Has Gone Platinum In 2014". Forbes.

- ^ Sanders, Sam. "Taylor Swift, Platinum Party of One". NPR.org.

- ^ "RIAJ Yearbook 2015: IFPI 2013, 2014. Global Sales of Recorded Music" (PDF). Recording Industry Association of Japan. p. 24. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ "Seagram Co Ltd - 'x-K405' for 6/thirty/00". SEC Info. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Midyear Digital Music Milestones". Recording Industry Association of America. July eleven, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

There's probably no one single reason, but nosotros'd similar to think that enhanced marketing efforts – like the auction of music at nontraditional outlets – and anti-piracy successes like the closure of LimeWire have helped.

- ^ a b Downloads neglect to stem fall in global music sales The Guardian

- ^ Press Release: "Digital Formats continue to drive the Global Music Market," IFPI (London, March 31, 2006).

- ^ "IFPI reveals 2007 recorded music revenues decline". Music Marry. May 15, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Global music sales downwards viii per centum in 2008: IFPI". Reuters. Apr 21, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "IFPI 2011 Report: Global Recorded Music Sales Autumn 8.4%; Eminem, Lady Gaga Summit Int'50 Sellers". Billboard. March 30, 2011. Retrieved Nov 21, 2016.

- ^ a b IFPI Digital Music Written report 2013: Global Recorded Music Revenues Climb for Start Fourth dimension Since 1999 Billboard

- ^ IFPI Digital Music Report 2014: Global Recorded Music Revenues Down 4% Billboard

- ^ Smirke, Richard (April 14, 2015). "Global Tape Business Dips Slightly, U.S. Ticks Upwards In IFPI'due south 2015 Written report". billboard.com . Retrieved Apr 20, 2015.

- ^ "IFPI Global Written report: Digital Revenues Surpass Physical for the Beginning Fourth dimension every bit Streaming Explodes". Billboard. April 12, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "IFPI Global Music Report 2016: State of the Manufacture" (PDF). Ifpi.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Streaming deemed for about half of music revenues worldwide in 2018". TechCrunch . Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ "GLOBAL MUSIC Report". IFPI . Retrieved August 21, 2020.

Sources [edit]

- Krasilovsky, G. William; Shemel, Sidney; Gross, John Yard.; Feinstein, Jonathan (2007), This Business of Music (10th ed.), Billboard Books, ISBN0-8230-7729-ii

Further reading [edit]

- Lebrecht, Norman: When the Music Stops: Managers, Maestros and the Corporate Murder of Classical Music, Simon & Schuster 1996

- Imhorst, Christian: The 'Lost Generation' of the Music Industry, published nether the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License 2004

- Gerd Leonhard: Music Like Water – the inevitable music ecosystem

- The Methods Reporter: Music Manufacture Misses Marker with Wrongful Suits

- Music CD Industry Archived June 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – a mid-2000 overview put together by Duke University undergraduate students

- Mario d'Angelo: "Does globalisation mean ineluctable concentration ?" in Roche F., Marcq B., Colomé D. (eds)The Music Manufacture in the New Economy, Report of the Asia-Europe Seminar (Lyon 2001) IEP de Lyon/Asia-Europe Foundation/Eurical, 2002, pp. 53–threescore.

- Mario d'Angelo: Perspectives de gestion des institutions musicales en Europe (Management Perspectives for Musical Institutions in Europe), OMF Series, Paris-Sorbonne University, Ed. Musicales Aug. Zurfluh, Bourg-la-Reine, 2006 ISBN two-84591-130-0

- Loma, Dave: Designer Boys and Material Girls: Manufacturing the [19]80s Popular Dream. Poole, Eng.: Blandford Press, 1986. ISBN 0-7137-1857-ix

- Rachlin, Harvey. The Encyclopedia of the Music Business. Starting time ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1981. xix, 524 p. ISBN 0-06-014913-2

- The supply of recorded music: A report on the supply in the Britain of prerecorded meaty discs, vinyl discs and tapes containing music. Contest Commission, 1994.

- Gillett, A. G., & Smith, G. (2015). "Creativities, innovation, and networks in garage punk stone: A instance study of the Eruptörs". Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts. four (1): 9–24. doi:10.1353/artv.2015.0000. ISSN 2164-7747. S2CID 54907273. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tschmuck, Peter: Creativity and Innovation in the Music Manufacture, Springer 2006.

- Knopper, S., 2011. The New Economics of the Music Industry. Rolling Stone, 25.

External links [edit]

- Salon commodity on Courtney Love's criticism of record industry business practices

- Federal Merchandise Commission printing release regarding price fixing

- Antitrust settlement in Nevada price-fixing instance

- Songwriter Janis Ian's critique of the tape manufacture's policies

- The Net is the Independent Artist'southward Radio – August x, 2005 MP3 Newswire article

- Music Downloads: Pirates- or Customers?. Silverthorne, Sean. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, 2004.

- The British Library - Music Industry Guide (sources of information) Archived Oct 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- The ASCAP Resource Guide: Recording Manufacture

- BPI: Music business – Industry Construction

- Academic manufactures about the music industry The Music Concern Journal

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_industry

Posted by: walkerproke1945.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Has The Music Industry Been Affected By Digital Downloading And Streaming"

Post a Comment